|

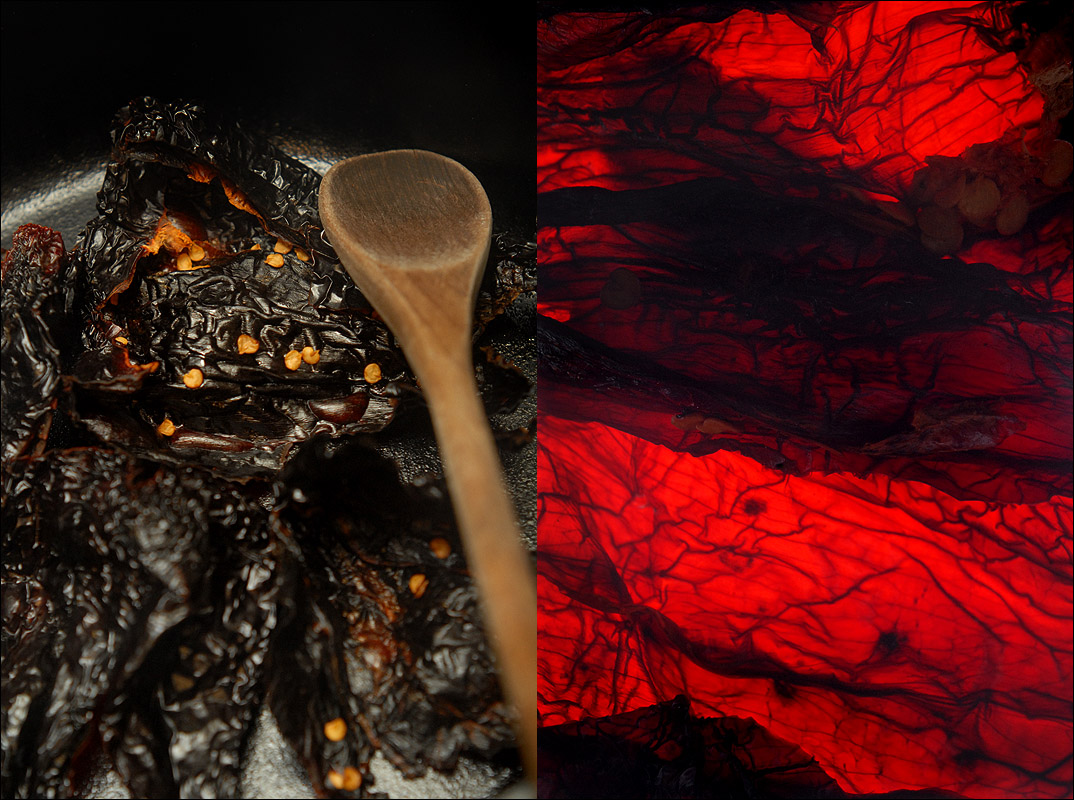

| (Vegetarian) Red #43. © Ryan Schierling |

According to legend and lore, chili was first made in Texas some time in the mid-1800s, in San Antonio. It was not much more than dried beef, beef suet, dried chili peppers (usually chile piquin) and salt, which were pounded together into trail-friendly bricks that could be rehydrated by boiling.

Always researching, I found a well-read but autographed fourth-edition 1972 copy of Frank X. Tolbert's "A Bowl of Red" at Half-Price Books, and have been working my way through lovingly-told tales of the history of chili con carne. It is a Texas education of the highest order.

Today, I am working a "vegetarian" batch that includes: Two pounds of small red beans. Six ancho chiles, toasted in a cast iron skillet, seeded and rehydrated for 20 minutes in boiling water, then pureed with a cup of the soaking liquid. Eight fresh serrano chiles, chopped with seeds and membranes intact. Five long sweet red peppers, seeded and chopped. Four homely little farmers market red bells, seeded and chopped. Three small onions, diced. One head of garlic, minced. One 28 oz. tin of Cento petite diced tomatoes. 16 oz. of beef stock. A cup of black coffee for me, and one for the chili. A shot of tequila for me, and one for the chili. A palmful of dried Mexican oregano. Cumin. A hit of Saigon cinnamon. A good squeeze of agave. Salt. Lime juice and minced fresh cilantro.

Depending on where you are from, it might not be your chili, but it is one of a million good chili variants out there. I have come a long way from my roots, and from the roots of Texas chili, but I know the efforts a proper chili recipe takes and the efforts a proper chili cook undertakes. And I supremely respect that.

I recently received a copy of Frank X. Tolbert's book as well, and to my surprise, it is also autographed as yours is. Have you read the other two books in what many consider to the the "holy trinity" of chili books? They are:

ReplyDeleteThe Great Chili Confrontation by H. Allen Smith (which I've read)

With Or Without Beans by Joe E. Cooper (which I have not read)

These might be some good additions to your library, if you are into food history/anthropology like I am.

"The Great Chili Confrontation" looks like an easy find, but that 1952 "With Or Without Beans" is $250 on Amazon.com! 1 copy available! That's got to be a serious holy grail kind of tome... going to have to scour the Goodwills and thrift shops here in Austin and see what I can find. Thanks for the tip.

Delete